- A.1 Preparation and Format

- A.2 Annotation Tasks and Procedure

- A.3 Identifying the Main Predicate

- A.4 Annotating Discourse Markers

- A.4.1 Annotating Explicit Discourse Markers

- A.4.2 Annotation of implicit discourse markers

- A.4.3 Alternative Lexicalizations

- A.5 Relation Inventory

- A.5.1 Top-Level Organization

- A.5.2 Annotation Principles

- A.5.3 Overall hierarchy and diagnostic markers

- A.6 Individual Relations

- A.7 Troubleshooting

- A.8 Relation Mapping

- A.9 ReferencesAURIS Discourse Extension, Christian Chiarcos, University of Augsburg, Germany, draft version of 2023-11-28

The annotation of discourse relations adopts a different format and is thus described in an appendix to the AURIS guidelines.

Discourse relations or coherence relations represent relations that describe the semantic or pragmatic relation utterances in a discourse. They are an important device in the establishment of coherence in text comprehension, and are thus often (but not always) signalled by means of language specific cues, or discourse markers, e.g., conjunctions, adverbials and particles such as and, or, but or then. A speaker can use discourse markers to explicate a discourse relation to the addressee, or to assert a discourse relation that would contradict the addressee’s intuitions:

Often, it is assumed that discourse relations closely interact with the hierarchical organization of discourse, by establishing larger discourse segments (discourse units) that span multiple sentences which are then further connected by means of discourse relations with other discourse segments to constitute a coherent text. So far, AURIS remains agnostic about the hierarchical organization of discourse. Instead, we follow the approach of the Penn Discourse Treebank (PDTB, Prasad et al. 2007) and provide shallow discourse annotations only. Our guidelines are based on a synthesis of PDTB and ISO 24617-8 guidelines, so that existing PDTB-style annotations (as available for many languages), resp., discourse annotations in general (which have a ISO 24617-8 interpretation), can be mapped to AURIS.

We annotate discourse relations between sentences and thus annotate entire sentences, only. For this reason, manual discourse annotation is conducted on a different format, but using the same set of technologies (i.e., Spreadsheet Software).

Although complete sentences are the unit of annotation, the sentence may include material not relevant for the discourse relation at hand. Instead, annotators should focus on the main clause of the sentence. There is an exception for attribution verbs, for which the main clause of the attributed statement (i.e., the reported speech) is to be annotated.

Note that these guidelines are partially based on the Penn Discourse Treebank, which also accounts for intrasentential discourse relations. We thus still include examples of intrasentential relations in the definition of discourse relations. In the future, these are to be replaced by real-world intersentential corpus examples.

The Goal of the annotation is to annotate every sentence with one discourse relation. It is neither required nor expected that the annotation of discourse relations leads to a tree structure. The refer to the sentence that is annotated as the utterance, the sentence that it is linked to by the discourse relation as the (contextual) anchor. If a discourse relation is indicated by an explicit discourse marker, this is syntactically integrated with the utterance. Accordingly, the applicability of a discourse relation can be tested by means of a paraphrase or substitution test where a diagnostic discourse marker is inserted: If the insertion of a diagnostic discourse marker does not change the meaning of the utterance in its context, the corresponding discourse relation can be annotated. A list of diagnostic markers is provided in an appendix.

The order of anchor and utterance is flexible, but in many cases, the anchor precedes the utterance. For implicit discourse markers, the anchor should generally precede the utterance, explicit discourse can be used by the speaker to underline that the anchor follows the utterance. A notable special case is the first part of a paired discourse marker, such as On the one hand … . On the other hand …. Here, the first utterance, marked with on the one hand, takes the second as its anchor, whereas the second takes the first as its anchor. If an utterance carries more than one explicit discourse marker, we annotate the first discourse marker, only.

Note: This section is concerned with the annotation of discourse relations, i.e., semantic or functional relations between utterances. As for relations between discourse referents (coreference, Centering Transitions), this is subject to Sect. 5 of the AURIS guidelines.

Annotation is done using Spreadsheet software such as MS Excel or

LibreOffice. We provide automated pre-annotations as well as formulas to

dynamically populate the spreadsheet file. For annotating a file with

pre-annotations, say doyle_bask.14.tsv, please proceed as

follows:

discourse-template.xlsx to

doyle_bask.14.xlsx (take the name of your source file as a

basis)doyle_bask.14.tsv in your Spreadsheet software

(or, alternatively, in a text editor)doyle_bask.14.tsv

<CTRL>+A to

select allA1), press

<SHIFT>+<CTRL>+<END> to select table

datadoyle_bask.14.tsv

<CTRL>+Cdoyle_bask.14.xlsx in your Spreadsheet

softwareA3 (first cell, third line)doyle_bask.14.tsv into

doyle_bask.14.xlsx

<CTRL>+V3

G3, press

<SHIFT>+<END> to select all formulasG3 until the end of the table

G3, press

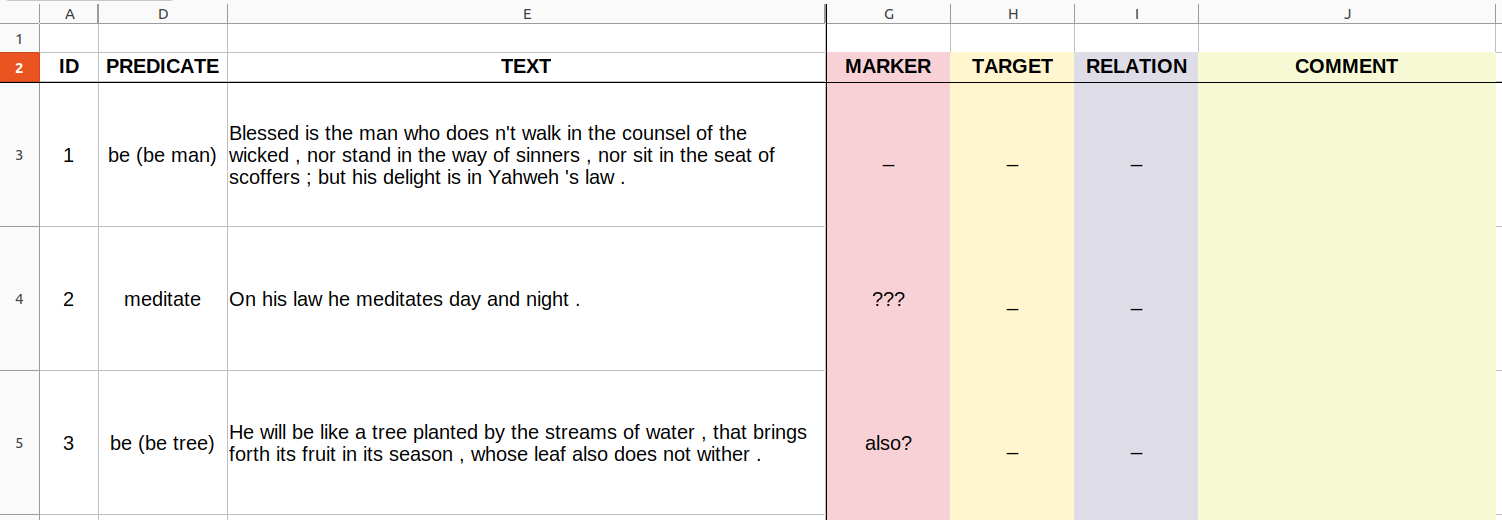

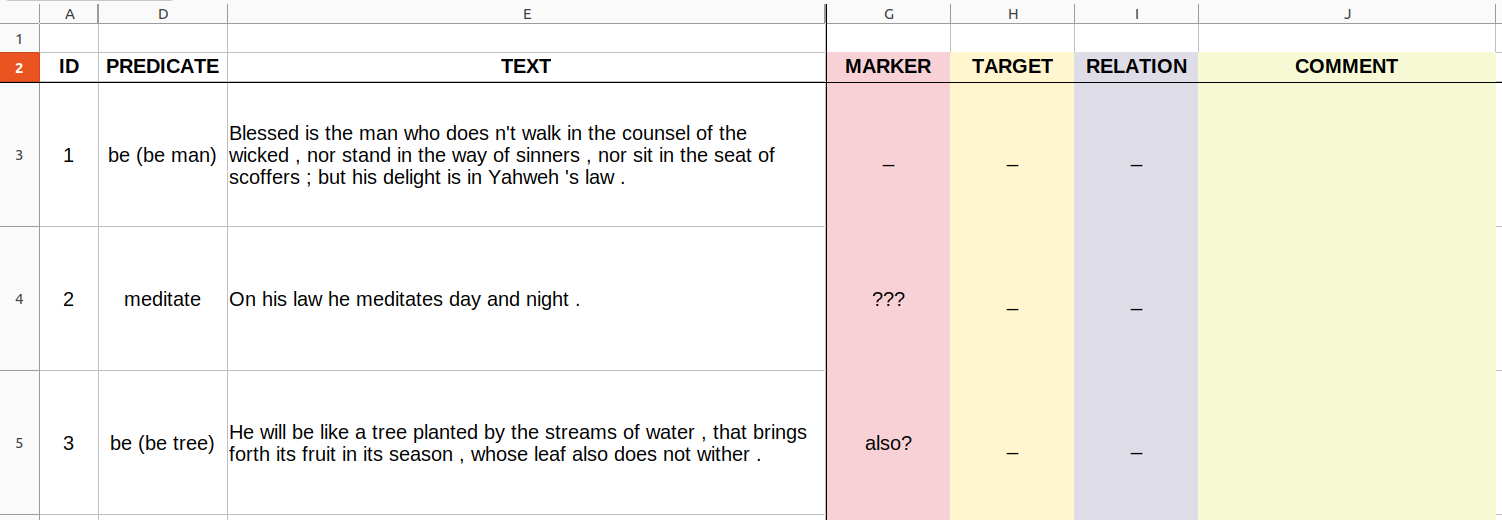

<SHIFT>+<CTRL>+<END><CTRL>+VAfter preparation, your table should look as follows:

(Note that you can resize column width and height as needed.)

Empty cells should be filled with _, automated

pre-annotations are marked with question marks. After annotations, no

question marks should remain.

The spreadsheet file contains the following columns:

ID (col A) sentence numberPREDICATE (col D) main verb, automatically

annotatedTEXT (col E) utterance to be annotatedMARKER (col G) possible discourse marker. Automatically

identified discourse markers are marked by a question mark. To be

replaced with actual discourse marker (without question mark).TARGET (col H) ID of the utterance that serves as

anchor of the discourse relation.RELATION (col I) discourse relationCOMMENT (col J) free-text commentNote that in the template, several columns are hidden. These are auxiliary columns that annotators don’t need to look into.

Also note that automated pre-annotations might be incorrect. Except

for MARKER (whose annotations should be replaced anyway),

correcting an incorrect pre-annotation requires to leave a comment,

either in an accompanying text file (annotation log), with reference to

the corresponding sentence ID, or in the COMMENT

column.

Annotation involves the following sub-tasks. Some of these tasks are

automated, however, automated annotations, if found to be incorrect,

should be corrected. In those cases, leave a comment in the

COMMENT column.

PREDICATE. If the annotator believes

the predicate to be incorrect, fix that column and leave a comment with

an explanation.MARKER)

MARKER. Should be manually confirmed

or revised.TARGET, identified by its numerical

ID. If there are multiple candidate anchors, annotate the closest

anchor.RELATIONMARKER, put it in round brackets to mark it as an implicit

discourse marker.MARKER) has been confirmed, annotate the

TARGET and the RELATION; continue in 5.COMMENT.COMMENT column to provide additional comments,

e.g., if no target and/or discourse relation could be established.Note: For 4.2.1 and 4.2.2, it seems most practical to answer these questions in tandem, i.e., to check first which discourse marker could be applied without having the text sounding unnatural and then identify the corresponding discourse relation on that basis. Inserting (or paraphrasing with) diagnosting discourse markers is an established technique for testing the applicability of a discourse relation. See Sect. A.4.2 for more detailed instructions.

For every sentence, we annotate the discourse relations of its core statement. Syntactically, the core statement is represented by the main predicate and its syntactic dependents. The main predicate is identified by the following rules:

Note 1: For syntactic analysis, we expect pre-annotation in accordance with Universal Dependencies 2.x. See there for the definition of syntactic heads.

Rule 3 is designed to rule out verbs of attribution as main predicates. Here, we follow ISO 24617-8 in excluding them from discourse annotation (if the sentence contains a reported statement). In (1), the discourse relation doesn’t hold between the communication acts (Mr. Edelman said X. Mr. Ackerman contended Y.) but between their respective statements (X, [implicit:Concession] Y). The respective main predicates are marked:

Discourse markers are cues that overtly mark discourse relations. For English, this primarily includes

We distinguish three kinds of discourse markers:

Explicit discourse markers are drawn from the following grammatical classes (Prasad et al. 2007):

adverbials (ADVP and PP):

DO NOT ANNOTATE adverbials modifying clauses other than the main predicate. In line with Universal Dependency syntax, the clause connected with the conjunction and in (4) is syntactically analyzed as a dependent of the first clause. It does thus not carry the main predicate and neither and nor as a result should be annotated.

coordinating conjunctions, but only if attached to the main predicate of an utterance:

DO NOT ANNOTATE conjunctions not modifying the main predicate:

subordinating conjunctions, but only if attached to the main predicate of an utterance:

DO NOT ANNOTATE conjunctions not modifying the main predicate:

If the main predicate carries more than one discourse marker, annotate the first discourse marker, only:

Here the, but and then encode independent discourse relations, the first indicating Concession, the second a temporal relation. However, but then can also be analyzed as a single discourse marker, indicating Concession:

Note that the first discourse marker may also occur at medial (or final) positions within a clause:

Adverbials should be annotated as discourse markers only if they establish a relation between utterance and anchor. Interjections such as well, focus markers such as anyway, and clausal adverbials such as strangely, probably, frankly, in all likelihood etc. are not annotated as discourse markers.

Note that not all words and phrases that can serve as discourse markers actually do so under all circumstances: Some tokens can also serve other functions, e.g., for can be a causal discourse marker (and then, be substituted with because), but it can also serve as a preposition indicating the beneficiary of an action. Likewise, discourse markers that serve to connect parts of the same utterance are beyond the scope of AURIS. Such expressions are not annotated as discourse connectives.

In the current workflow, the first candidate discourse marker is

automatically annotated. However, note that this has been heuristically

extracted and may include discourse markers not modifying the main

predicate, or expressions that could serve as discourse markers

but that don’t in this particular context. Thus, in the column

MARKER, these are always shown with a question mark and to

be confirmed (or replaced) by manual annotation. Discourse markers with

question marks are considered an error.

If an utterance does not feature an explicit discourse marker, annotators should try to test whether an explicit discourse marker could be inserted or whether another discourse relations applies. Example (14) shows an example of an implicit because inserted to connect two adjacent utterances

In discourse relations with implicit discourse markers, the anchor always precedes the utterance. In the following, it would be logically possible to annotate Reason to point from the first utterance to the second, but because of ordering preferences for implicit relations, we only annotate the inverse relation Result:

For annotating implicit discourse markers, annotators should use the list of discourse relations and their diagnostic discourse markers, and check it the order specified in Sect. BELOW.

Note: Unlike PDTB2, the annotation of implicit relations is not limited to adjacent utterances.

Many researchers distinguish discourse markers and alternative lexicalizations, i.e., a phrasal expression that conveys the meaning of a discourse marker that could be used in its place in a more or less equivalent way (e.g., This observation leads us to conclude that … in place of Thus, …). If such phrases are no longer than 5 words, annotators should annotate such phrases as explicit discourse markers. If such phrases are longer than 5 words, proceed as follows:

If the discourse marker you provided could also be used in addition to the alternative lexicalization, then treat this as implicit discourse marker, i.e.,

AURIS discourse relations are organized in a hierarchy that is also used to define selection preferences for annotation.

In addition to these, we use NoRel to mark utterances for which no anchor can be established.

if the main predicate carries more than one explicit discourse marker, annotate the first explicit discourse marker

if there is no discourse marker or the discourse marker is ambiguous with respect to the discourse relation it encodes:

annotate the most specific discourse relation possible, using the following preference hierachy

The logic behind this ranking is that it describes a spectrum from semantically highly constrained (i.e., very specific) to semantically less constrained (i.e., more generic) relation types, and that annotators should annotate the most specific discourse relation applicable.

EntRel relations are a

fallback to enable the annotation of discourse relations whose

attachment is unclear, but still evident from coreference links.If no relation can be established with the last preceding utterance, explore the one before, etc. Note that, as a result, the anchor of an utterance does not have to be in the preceding utterance:

In this example, the anchor of the implicit Contrast (16.5) is three sentences back (16.2).

For (17.3), no discourse relation, nor an entity relation can be established between with (17.2), so that (17.1) has to be considered (and can be confirmed) as anchor.

If an utterance can take more than one sentence as anchor, annotate the most proximate anchor, only:

According to Bunt et al. (2012), (19.5) actually refers back to (19.1) - (19.4), but we annotate only (19.4) as anchor. (19.7), then, takes scope over (19.1) - (19.4) and (19.6), but we only annotate the relation to (19.6).

The top level of the hierarchy follows PDTB2, the middle level represents SemAF relations, the third level represents SemAF attribute roles.

| discourse relation | diagnostic marker / paraphrase (comments) |

|---|---|

| ADVERSATIVITY | |

- Concession |

even though, although (also: but) |

- expectation-raiser |

even though, although (also: but; not: however) |

- contra-expectation |

however (also: even though, although, but) |

- concession |

(if directionality is unclear) |

- Contrast |

but (not: however, although) |

| CONTINGENCY | |

- Causal |

|

- reason |

because, a reason is that |

- result |

as a result (so) |

- cause |

(if directionality is unclear) |

- Conditional |

|

- condition |

if |

- consequence |

then, so, under this condition |

- Negative_Condition |

|

- neg_condition |

unless |

- neg_consequence |

otherwise |

- Purpose |

|

- goal |

in order to |

- enablement |

for that purpose, therefore |

| TEMPORAL | |

- Synchrony |

while, when |

- Asynchrony |

|

- before |

before (that) |

- after |

after (that), then (temporally) |

| EXPANSION | |

- Manner |

|

- means |

(intrasentential: by, the manner of/in which/by which |

- achievement |

thereby |

- Exception |

|

- regular |

(otherwise) |

- exception |

(instead, rather) |

- Substitution |

instead (of) |

- disfavoured |

rather than |

- favoured |

rather |

- Similarity |

similarly, like, also; as well |

- Conjunction |

in addition, additionally, further (and) |

- Disjunction |

or |

- Exemplification |

|

- set |

(more) generally, in general |

- instance |

for example, for instance, in particular, specifically |

- Elaboration |

|

- broad |

in sum, in short, overall, finally |

- specific |

specifically, indeed, in fact |

- Restatement |

in other words |

- Hypophora |

(anchor is a rhetorical question) |

- Attribution |

(verbs of attributions, if detached by sentence splitting from reported statement) |

| DIALOG | (only if turn-taking occurs) |

- Functional-Dependence |

(sub-classified for communicative functions) |

- answer |

yes, no (factual answers, anchor is question) |

- agreement |

Exactly! (anchor is a statement) |

- disagreement |

no (anchor is a statement) |

- offer |

I will do … (anchor is a request) |

- address-suggest |

(anchor is a suggestion) |

- dependent-act |

(other communicative function) |

- Feedback |

(turn-taking not initiated by the addressee) |

| EntRel | (no relation other than coreference between utterance and anchor) |

TODO: add diagnostic markers, assert annotation preference, check preferential order

When annotating discourse relations, choose the most specific relation possible.

ADVERSATORYDiscourse relations concerned with highlighting differences between the situations described in the utterance and the anchor.

ConcessionConcession is used when an causal relation expected from

one of the arguments is cancelled or denied by the situation described

in the other. Concession is related to CONTRAST in that it highlights a

difference between utterance and anchor. Semantically, the connective

indicates that one of the sentences describes a situation A which causes

C, while the other asserts (or implies) ¬C. Alternatively, one sentences

denotes a fact that triggers a set of potential consequences, while the

other denies one or more of them (cf. Bunt & Prasad 2016, Prasad et

al. 2007, p.32,34; Webber et al. 2019a, p.24). Diagnostic discourse

markers (either at the expectation-raiser or the

contra-expectation argument) are although or

even though, a diagnostic discourse marker at

contra-expectation is however. Note that

but, taken as diagnostic discourse marker of

Contrast is usually also applicable to

Concession. Annotate Concession for cases in

which however can be used in place of but.

Note that concessive connectives can also be used in a rhetorical or pragmatic way where their semantic conditions do not hold. Such cases of “apparent Concession” are included here, as well, but MUST be documented in comments. This includes cases in which the speech act associated with the

expectation-raiseris cancelled or denied by thecontra-expectationor its speech act. So far, this has been observed forcontra-expectation, only (Webber et al., 2019, p.24, PDTB3 Comparison.Concession+SpeechAct).

expectation-raiserThe utterance creates an expectation (a situation that is expected to cause the situation described in the other argument) that is cancelled or denied by the anchor. The main diagnostic discourse marker is although (PDTB “expectation”, Prasad et al. 2007, p.34, Webber et al. 2019a, p.23-24, Bunt & Prasad 2016).

(20.1) It’s as if investors, the past few days, are betting that something is going to go wrong – even if they don’t know what. (PDTB3, wsj 0359)

(20.2)

contra-expectationThe utterance cancels or denies a situation that is expected after processing the anchor (cf. Prasad et al. 2007, p.34). A diagnostic discourse marker however.

(21.1) Last Friday, 96 stocks on the Big Board hit new 12-month lows. But by Mr. Granville’s count, 493 issues were within one point of such lows. (PDTB3, wsj 0359)

(21.2) American Brands “just had a different approach,” Mr. Wathen says. [Implicit=however] “Their approach didn’t work.” (PDTB3, wsj 0305)

Contra-expectation also applies to cases in which

concessive connectives are used in a rhetorical or pragmatic way where

their semantic conditions do not hold (cf. Prasad et al. 2007, p. 27).

Such cases of “apparent Concession” MUST be documented in comments.

concessionAnnotate utterances whose discourse relation is ambiguous between

“expectation” and “contra-expectation”, or where the context or the

annotators’ world knowledge is not sufficient to specify the subtype as

concession (Prasad et al. 2007, p.34).

ContrastIn Contrast, the utterance and the anchor share a

predicate or property and a difference is highlighted with respect to

the values assigned to the shared property. The truth of both arguments

is independent of the connective or the established relation, i.e.,

neither argument describes a situation that is asserted on the basis of

the other one, and thus, there is no directionality in the

interpretation of the arguments (Bunt & Prasad 2016, Prasad et

al. 2007, p.32). This is the main difference in comparison with the

otherwise similar Concession relation. A diagnostic

discourse marker for contrast is but.

This includes cases of juxtaposition, in which the connective indicates that the values assigned to some shared property are taken to be alternatives as in (23.4).

This also includes cases of opposition, in which the connective indicates that the values assigned to some shared property are the extremes of a gradable scale, e.g., tall-short, accept-reject, etc.

Note that explicit discourse markers can also be used to underline a “pragmatic” contrast relation that does not hold between utterance and anchor, but between one of the arguments and an inference that can be drawn from the other, in many cases at the speech act level, as in (23.6).

If annotators face difficulties to distinguish

ConcessionandContrast, check by paraphrasing with although or however, whether a causal relation that is expected on the basis of one argument is denied by the other. If this is possible, annotateConcession, if not, annotateContrast.

In a Causal relation, one argument (reason)

provides a reason, explanation or justification for the situation

(result) described in other to come about or occur (cf. ISO

24617-8 CAUSE, Bunt & Prasad 2016; Webber et al. 2019a, p.19).

reasonThe utterance prodives the reason (cause, explanation or justification) for the situation described in the anchor, as typically expressed with the connective because (cf. PDTB2 Reason, Prasad et al. 2007, p.26, 29; Webber et al. 2019a, p.19).

Note that in (24.5), we do not annotate a DIALOG

relation because an overt discourse markers indicates a higher-ranking

discourse relation.

The reason relation also includes epistemic, rhetorical

or pragmatic uses of causal connectives, e.g., where the utterance

provides justification for a claim expressed in the anchor, as marked,

for example, with the connective because:

resultThe situation described in the utterance is interpreted as the result (effect) of the situation presented in the anchor. A diagnostic discourse marker is as a result (cf. PDTB Result, Prasad et al. 2007, p.26,29; Webber et al. 2019a, p.20).

(25.1) Now, though, enormous costs for earthquake relief will pile on top of outstanding costs for hurricane relief. “That obviously means that we won’t have enough for all of the emergencies that are now facing us, and we will have to consider appropriate requests for follow-on funding,” Mr. Fitzwater said. (PDTB3, wsj 1824; Prasad and Bunt 2015)

(25.2) “We are going to explode lower,” says the flamboyant market seer, . . . [Implicit=so] Anyone telling you to buy stocks in this market is technically irresponsible. (PDTB3, wsj 0359)

The relation result also applies to episthemic uses of

causal markers, when the anchor gives the evidence justifying the claim

given in the utterance:

Likewise, result is to be used when the anchor is the

reason for the speaker to produce the (speech act represented by the)

utterance:

Note: PDTB3 introduced Cause/negative-result for intrasentential relations, specifically for the English construction too X to Y (Webber et al. 2019a, p.18,20). This does not seem to be relevant for intersentential relations.

causeFor causal relations between utterance and anchor, annotators should

normally apply reason or result. Only if the

annotators could not uniquely specify the directionality, they should

use cause, instead.

ConditionalA Conditional relation relates a hypothetical

(unrealized) scenario with its (possible) consequence. The consequence

is a situation that holds when the condition is true. Unlike

Causal relations, the truth value of the arguments of a

Conditional relation cannot be determined independently of

the connective. (PDTB Condition, Prasad et al. 2007, p.26,29; SemAF

CONDITION).

conditionThe utterance represents a condition, an unrealized

situation which, when realized, would lead to the consequence described

in the anchor. If the utterance holds true, the anchor is caused to hold

true at some instant in all possible futures. This can be a generic

truth about the world, a statement that describes a regular outcome

every time the condition holds true, or a single time that this is the

case. Following ISO 24617-8, this is independent of whether the

consequence is believed to be true (factuals) or not

(counterfactuals). If the condition is not true, the anchor should

express what the consequences would had been if it had (Prasad et

al. 2007, p.30-31; Bunt & Prasad 2016). A diagnostic discourse

marker is if.

Condition also includes rhetorical or pragmatic uses of

conditional constructions whose interpretation deviates from the

standard semantics, e.g., cases of explicit if tokens where

utterance and anchor are not causally related, but presented as if they

were. In these cases, the anchor holds true independently of the anchor,

there is no causal relation between the two arguments:

relevant context information: The utterance provides the context in which the description of the situation in anchor is relevant. A frequently cited example for this type of conditional is (113). (To be replaced by an intersentential relation.)

implicit assertion: refers to a special use of if-constructions when the conditional involves an (implicit) assertion. In (26.3), the utterance (O’ Connor is your man) is not a consequent state that will result if the condition expressed in the anchor holds true. Instead, if is used to implicitly assert that O’Connor will keep the crime rates high. (To be replaced by an intersentential relation.)

consequenceThe anchor represents a condition, i.e., an unrealized situation

which, when realized, would lead to the consequence

described in the utterance. As for the logical relation between

condition and consequence, the same conditions hold as described above

(cf. Bunt & Prasad 2016). A diagnostic paraphrase is under this

condition, possible discourse markers are then and

so (which can also be used for temporal and causal

relations).

Negative ConditionOne sentence represents an unrealized situation (negated condition) which, if it does not occur, would lead to the consequent described in the other (Bunt & Prasad 2016; Webber et al. 2019a, p.23).

Note: It is possible that this is not an intersentential relation. In PDTB2, unless would normally be annotated as EXPANSION/Alternative/disjunctive, but Bunt and Prasad (2016) explicitly link it with PDTB2 Condition, instead. PDTB3 introduced CONTINGENCY/Negative Condition for intrasentential relations (Webber et al. 2019a, p.18).

neg_conditionThe utterance describes an unrealized situation which, when not

realized, leads to the Consequence described in the anchor.

A diagnostic discourse marker is unless.

(28.1) But a Soviet bank here would be crippled unless Moscow found a way to settle the $188 million debt, which was lent to the country’s short-lived democratic Kerensky government before the Communists seized power in 1917. (Webber et al. 2019a, p.23, INTRASENTENTIAL)

(28.2) Sandoz said it expects a ”substantial increase” in consolidated profit for the full year, barring major currency rate change. (PDTB3, wsj 2089, INTRASENTENTIAL)

This also includes episthemic uses of conditional discourse markers, esp., when the consequent is an implicit speech act.

neg_consequenceThe anchor describes an unrealized situation which, when not realized, leads to the negative consequence described by the utterance. A diagnostic discourse marker is otherwise.

PurposeIn a Purpose relation, the goal enables the

enablement, i.e., one sentence presents an action that an

AGENT undertakes with the purpose of the GOAL conveyed by the other

sentence being achieved. Usually (but not always), the agent undertaking

the action is the same agent aiming to achieve the goal (Bunt &

Prasad 2016; Webber et al. 2019a, p.21). This relation is similar to

Causal and Conditional relations, the main

difference is that the former are neutral with respect to individual

engagement whereas Purpose relations presume some level of

agency on behalf of the speaker, the hearer or another agent addressed

or involved in the situation described. Purpose requires a

volitional agent, a diagnostic marker for the goal role is

in order to, a diagnostic marker for the

enablement is for that purpose (Webber et

al. 2019b).

Note: In PDTB2, purpose seems to have been grouped together with Cause and Condition. PDTB3 introduced Purpose specifically for intrasentential relations (Webber et al. 2019a, p.18). It is thus possible that it does not apply to intersentential relations.

goalThe utterance represents a goal (purpose) enabled by the situation described in the anchor, i.e., the action undertaken to achieve the goal (Webber et al. 2019a, p.21). All PDTB3 examples are intrasentential. This is possibly not relevant for AURIS.

enablementThe utterance describes a situation that enables the goal (purpose) described in the anchor, i.e., the action undertaken to achieve the goal (Webber et al. 2019a, p.21). A diagnostic marger is for that purpose.

TEMPORALSynchronySynchrony applies if the situations described in the

utterance and the anchor have some degree of temporal overlap, i.e., if

the two situations started and ended at the same time, if one was

temporally embedded in the other, or if the two crossed. Diagnostic

connectives are while and when (Bunt & Prasad

2016; PDTB2 Synchronuous in Prasad et al. 2007, p.27-28).

The utterance stands in a temporal order with the situation described in the anchor (Bunt & Prasad 2016, Prasad et al. 2007, p.27).

beforeThe situation described in the utterance temporally precedes the situation described in the anchor. A diagnostic discourse marker is before (that) (Bunt & Prasad 2016; Prasad et al. 2007, p.28).

afterThe situation described in the anchor temporally precedes the situation described in the utterance (Bunt & Prasad 2016; Prasad et al. 2007, p.28). Diagnostic discourse markers are after (that) and then (temporal).

EXPANSIONConjunctionIn Conjunction, utterance and anchor feature the same

relation to some other situation evoked in the discourse. As an example,

this includes a list, defined in prior discourse, where

Conjunction is the relation between the list elements. A

discourse marker for conjunction indicates that utterance and anchor, or

the entities mentioned therein are doing the same thing with respect to

that situation (Bunt & Prasad 2016). The situation described in the

utterance provides additional, discourse new, information that is

related to the situation described in the anchor, but not in any other,

more specific discourse relation. The semantics are thus no more than

that of a logical ∧ (and). Diagnostic connectives are also,

in addition, additionally, further, etc.

(Prasad et al. 2007, p.37; Webber et al. 2019a, p.25-26). A frequent

discourse marker is also and, but note that this is ambiguous

between this and other discourse relations.

Note: Because of the largely underspecified semantics, this must be annotated after any more specific relation has been tested for.

DisjunctionIn Disjunction, utterance and anchor denote alternative

situations that bear the same relation to some other situation evoked in

the discourse and that make a similar contribution with respect to that

third situation (Bunt & Prasad 2016; Prasad et al. 2007, p.36;

Webber et al. 2019a, p.26). We do not distinguish as to whether both

situations can hold simultaneously (logical or) or they are mutually

exclusive (exclusive or). A diagnostic discourse marker is

or.

RestatementIn Restatement, the utterance describes the same

situation as the anchor, but from a different perspective, e.g., when

describing the same situation as presented before using the speaker’s

own words (Bunt & Prasad 2016; PDTB2 Restatement/equivalence, Prasad

et al. 2007, p.35-36, Webber et al. 2019a, p.26). A diagnostic discourse

marker is in other words.

ExceptionIn Exception, the regular evokes a set of

circumstances in which the described situation holds, while the

exception indicates one or more instances where it doesn’t

(Bunt & Prasad 2016; Webber et al. 2019a, p.27).

Note: Intutitively, this involves an element of contrast, but we follow PDTB2 in considering it a form of PDTB EXPANSION.

regularThe utterance evokes a set of circumstances in which the described situation holds, while the anchor represents an exception, i.e., it indicates one or more instances where it doesn’t (Bunt & Prasad 2016).

Note: It is yet to be confirmed whether this relation exists in AURIS, as it requires a discourse marker to mark the regular rather than the exception. It could exist in cases in which paired discourse markers (like either … or or on the one hand … on the other hand) mark

EXCEPTIONrelations.

exceptionThe utterances specifies an exception to the generalization specified by the anchor. In other words, the situation described in the anchor is false because the sitation described in the utterance is true (but if the utterance were false, the anchor would be true), cf. (Prasad et al. 2007, p.36). According to PDTB2, possible discourse markers are instead or rather – both of these are, however, more regularly used with other discourse relations, so that they are not diagnostic discourse markers.

ExemplificationIn Exemplification, one sentence describes a set of

situations; the other an element of that set (Bunt & Prasad

2016).

setThe utterance describes a situation as holding in a set of circumstances, while the anchor describes one or more of those circumstances (Webber et al. 2019a, p.27). Diagnostic discourse markers include (more) generally or in general:

instanceThe utterance provides one or more instances of the circumstances described by the anchor. The anchor evokes a set and the utterance describes it in further detail. It may be a set of events, a set of reasons, or a generic set of events, behaviors, attitudes, etc. Diagnostic discourse markes are for example, for instance, in particular and specifically (Prasad et al. 2007, p.34; Webber et al. 2019a, p.27).

ElaborationBoth sentences describe the same situation, but in less or more detail (Bunt & Prasad 2016; PDTB3 Level-of-Detail in Webber et al. 2019a, p.27).

broadThe utterance describes the same situation as the anchor, but the anchor provides more detail. Typically, the utterance summarizes the anchor, or in some cases expresses a conclusion or generalization (Bunt & Prasad 2016; PDTB2 Restatement/generalization in Prasad et al. 2007, p.35). Diagnostic discourse markers include in sum, in short, overall, and finally.

specificThe utterance describes the situation described in the anchor in more detail. Diagnostic discourse markers include specifically, indeed and in fact (Prasad et al. 2007, p.35).

MannerIn Manner, the means argument describes a

way in which the achievement comes about or occurs (Bunt

& Prasad 2016). Manner answers “how” questions such as “How were the

children playing?” (Webber et al. 2019a, p.28).

Note: As PDTB3 introduced Manner specifically for intrasentential relations, it is yet to be confirmed whether this is a relevant category for AURIS. Also note that Webber et al. 2019a (p.28) emphasized that manner is typically accompanied by other relations (Purpose, Result or Condition).

meansThe utterance describes the means, i.a. a way in which the achievement presented in the anchor comes about or occurs (Bunt & Prasad 2016). For intrasentential manner relations, a diagnostic discourse marker is by, a diagnostic paraphrase is the manner of/in which/by which (Webber et al. 2019a, p.29-30).

achievementThe anchor describes a way in which the achievement described in the utterance comes about or occurs (Bunt & Prasad 2016). A diagnostic discourse marker is thereby.

SubstitutionTwo mutually exclusive alternatives are evoked in the discourse but

only one is taken, the other is ruled out. A diagnostic discourse marker

is the connective instead (PDTB2 chosen alternative, Prasad et

al. 2007, p.36; Webber et al. 2019a, p.29-30). To some extent, the same

discourse markers can be used for Substitution and

Exception, the difference is that Exception is

an observation and grounded in facts, whereas Substitution

involves a conscious choice or preference.

disfavoured-alternativeIn comparison with the favoured alternative presented in the anchor, the situation described in the utterance is disfavored or rejected alternative (Bunt & Prasad 2016). A diagnostic discourse marker is the connective rather than.

favoured-alternativeIn comparison with the disfavoured alternative presented in the anchor, the situation described in the utterance is favored, and the alternative presented in the anchor is rules out (Bunt & Prasad 2016, Webber et al. 2019a, p.30). A diagnostic discourse marker is the connective rather.

Note: Following Bunt and Prasad (2016), this is grouped under PDTB Expansion. However, RST Antithesis is much more defined along the lines of contrast, so, it might be better put there?

SimilarityIn Similarity, one or more similarities between the

utterance and the anchor are highlighted with respect to what each

predicates as a whole or to some entities they mention (Bunt &

Prasad 2016; Webber et al. 2019a, p.25). Diagnostic discourse markers

include similarly, like or also. We also take

the discourse marker as well to designate

Similarity.

Note:

Similarityis closely related toConjunction. AnnotateSimilarityif an element of comparison (but not contrast) is involved, annotateConjunctionis no such aspect is to be found.

HypophoraHypophora is used when the utterance represents an answer to a

rhetorical question presented in the anchor. If there is a semantic

discourse relation connecting the situation described with another

anchor in the discourse, annotate this as the relation of the question

(the anchor of Hypophora). The diagnostic criterion is that

the anchor has the form of a question, that the answer is immediately

provided by the speaker and that no answer from the addressee is

expected.

Note that this also includes reported answers as in (48.2).

AttributionWe do not consider attribution a discourse relation in its own right.

However, as we perform sentence-level annotation over pre-determined

sentence splits, it is possible that an attribution phrase gets detached

from the reported statement. In those cases, annotate the utterance

expressing the attribution with an Attribution relation

that takes the statement (resp., its closest sentence) as anchor:

Note that example (49) originally had a paragraph break between the attribution sentence and the statement.

DIALOGDialog relations are to be annotated if and only if turn-taking between multiple speakers applies and no other discourse relation is explicitly signalled. In this case, annotate the discourse function.

We follow ISO 24617-8 (Bunt et al. 2012, p.431; Bunt et al. 2019) in distinguishing two kinds of turn-taking relations:

Note: AURIS dialog relations are only to be annotated if they occur after turn-taking and no other discourse relation applies. Dialog relations do not apply when the subsequent text relates to a question in other ways – for example, in the case of rhetorical questions that are posed for dramatic effect or to make an assertion, rather than to elicit an answer (Webber et al. 2019a, p.9). Rhetorical questions are excluded from this group and to be annoted as

Hypophora, instead.

Functional dependenceIn Functional dependence, the utterance is a dialogue

act that is responsive in nature and that address the information

communicated in the utterances; the anchor is the dialogue act that the

utterance responds to (Bunt & Prasad 2016, Bunt et al. 2019).

Diagostic paraphrases include (semantically empty) responses such as

“Yes”, “No thanks”, “No problem”, and “OK” (Bunt et al. 2012, p.432). In

AURIS, functional dependence relations involve the explicit elicitation

of the response as an anchor – either directly by a question, request or

suggestion, or indirectly with a statement that the addressee reacts

to.

Following ISO (2010; cf. Bunt et al. 2018, 2019), the following

communicative functions are relevant and should be annotated in AURIS as

sub-types of functional dependence: Answer,

Offer, Address Suggest,

Agreement, Disagreement

answerThe utterance is a dialog act performed by the speaker in order to make the information in the utterance known to the addressee in response to the anchor. The anchor expresses an information-seeking function (e.g., a question). The speaker believes the utterance to be correct (ISO 2010, Bunt et al. 2018, 2019). If an answer involves feedback particles like yes, no or perhaps, these should be annotated as explicit discourse marker. Do not annotate an implicit discourse marker.

We do not differentiate types of asnwers. However, note that we

distinguish answers that address an information need from responses to

requests for a particular action. Both can take questions as their

anchors, but a commitment (or denial) of future actions on behalf of the

speaker is to be annotated as Offer.

agreementThe anchor describes a situation that the speaker presents as a true statement. With the utterance, the addressee confirms that he believes that this statement is indeed true (ISO 2010). Use if the utterance can be paraphrased by “Exactly!”.

The agreement relation is similar to (a positive)

answer in that it addresses an information need of the

addressee, for the case of Agreement, however, it is not solicited by a

question, but by a speech act that invites a (positive) feedback

response.

disagreementThe anchor describes a situation that the speaker presents as a true statement. With the utterance, the addresee informs the speaker that he believes that this statement is false (ISO 2010).

The agreement relation is similar to a negative

answer in that it addresses an information need of the

addressee, for the case of Agreement, however, it is not solicited by a

question, but by a speech act that is refuted by the speaker.

offerWith the utterance, the speaker commits himself to perform a particular action. The speaker assumes that the addressee refers the action to be performed. The anchor is the sentence that caused the speaker to assume that the addressee wants him to perform the offered activity (ISO 2010, Bunt et al. 2018, 2019).

Note: We only annotate solicited offers that are performed in response to a request.

We do not differentiate different kinds of offers, such as promises or accepting requests:

Offers also includes a negative response to requests (i.e., declined requests):

In Alibaba’s response, the first statement directly responds to the

preceding sentence, but is subsequently elaborated into a refined offer.

Note that this elaboration is to be modelled by EXPANSION

relations that take Not now as their anchor, not directly as

feedback responses to the statements of Unknown ID.

address-suggestWith the utterance, the speaker commits himself (or declines) to

perform an action that was suggested to him. The anchor is an utterance

of the addressee that made the speaker believe that was a suggested

action. The main difference to offer is that the addressee

is neutral about his proposal or that the speaker himself is the main

beneficiary of the proposal (ISO 2010, Bunt et al. 2018, 2019).

We include both positive and negative responses to suggestions under

address-suggest.

dependent-actIf an utterance dialog act is in response to the content of an

utterance by the addressee but none of the aforementioned communicative

functions applies, annotate as dependent-act and leave a

comment.

FeedbackFeedback utterances are about the processing of a communicative event that occured earlier in the discourse.

In a Feedback relation, the utterance provides or

elicits information about a communicative event (by one of the other

dialogue participants) that occurred earlier in the discourse. Feedback

expressions include OK, Uh-huh, Really?, but

also something like Tuesday? or What did you say? As

with Entity Relations, no explicit or implicit connective is identified

and annotated: The only elements of the relation are the utterance and

the anchor (Bunt et al. 2012, Bunt & Prasad 2016, Bunt et

al. 2019).

Note: The difference between feedback dependence and functional dependence is that feedback dependence is not solicited by the speaker. We do not distinguish communicative functions of feedback relations. Another difference to functional dependence is that the semantic content of a feedback act may be determined by what was said before rather than by the semantic content of a previous dialogue act.

Feedback includes phenomena such as clarification questions (55.1) and confirmation of comprehension by direct responses (55.2) or repetition (last line in 55.3), but not direct expressions of agreement or disagreement.

(55.1) A: I would like to come on Tursday. [Feedback] B: On Thursday? (Bunt et al. 2012, p.433)

(55.2) A: That’s at two-thirty. [Feedback] B: I see. (Bunt et al. 2012, p.433)

(55.3)

EntRel: Entity

relationsIf no other discourse relation can be annotated, but the utterance

stands in an entity-based coherence relation with the anchor (i.e.,

anchor and utterance contain referring expressions that stand in an

anphoric/coreferential relation with each other), then annotate an

entity relation (EntRel).

In an entity relation, the utterance provides further description about some entity or entities introduced in the anchor, expanding the narrative forward of which the anchor is a part, or expanding on the setting relevant for interpreting the anchor. Utterance and anchor describe distinct situations, and the anchor may seen as a “foreground” that introduces the entities elaborated in the utterance (Bunt & Prasad 2016). Entity relations are not marked by explicit discourse markers, but defined by coreference between their referrring expressions, the anchor must always precede the utterance.

If an entity relation holds between the utterance and several candidate anchors (as in ex. 56.2), annotate the relation to the closest anchor candidate:

BIS HIER

pairwise discourse markers: Annotate independently. As both parts refer to each other, this creates a cycle in the annotation.

discourse markers of attribution verbs: If a discourse marker is (correctly or not) attached to an attribution verb, but the main predicate of an utterance is a dependent of the attribution verb, this discourse marker is taken to refer to the main predicate. The primary discourse marker is identified by means of the following preferences:

MAIN CLAUSE > DEPENDENT CLAUSE > DEPENDENT of DEPENDENT CLAUSE

within a clause: first > second

(57.1’) On the one hand, Mr. Front says, it would be misguided to sell into “a classic panic.”

Apparent cases of multiple utterance. In the following example, utterances 4.-7. constitute an elaboration of 3. However, we adopt the SDRT view on such constellations, that is, if 4 elaborates 3 and 5 elaborates 3, a narration relation hold between 4 and 5. Because we annotate the closest anchor for each utterance, only the narration is to be annotated, but not the elaboration. (Note that these are SDRT relations, but the argumentation holds for ISO 24617-8 labels, as well.)

(57.2) 1. Legal controversies in America have a way of assuming a symbolic significance far exceeding what is involved in the particular case. 2. They speak volumes about the state of our society at a given moment. 3. It has always been so. 4. [Implicit = for example] In the 1920s, a young schoolteacher, John T. Scopes, volunteered to be a guinea pig in a test case sponsored by the American Civil Liberties Union to challenge a ban on the teaching of evolution imposed by the Tennessee Legislature. 5. The result was a world-famous trial exposing profound cultural conflicts in American life between the “smart set,” whose spokesman was H.L. Mencken, and the religious fundamentalists, whom Mencken derided as benighted primitives. 6. Few now recall the actual outcome: 7. Scopes was convicted and fined $100, and his conviction was reversed on appeal because the fine was excessive under Tennessee law. (PDTB2, 0946)

multiple clauses as anchors: In AURIS, the anchor must be a single utterance (resp., its main predicate). If a discourse connective seems to take a sequence of utterances as anchors, chose the closest candidate anchor with which a relation can be established. However, plausibility overrides proximity. In the example below, the third sentence could is in a contrast relation with the first as well as the second. However, the second seems to elaborate with anecdotal evidence on the first, so the main reason for surprisal in the third utterance is not the karaoke ban, but the general poor condition. So, annotate 1 as an anchor. (The situation may be different if karaoke is the main topic of the article.)

Note: This is different from PDTB, where, instead, a minimality principle applies.

attribution: As defined by Prasad et al. (2007, p.40), attribution is “a relation of “ownership” between abstract objects and individuals or agents. That is, attribution has to do with ascribing beliefs and assertions expressed in text to the agent(s) holding or making them”. If a the main clause of an utterance expresses an attribution, with a statement in a dependent clause or direct speech annotated as part of the same utterance, then the main predicate of the utterance is to be taken from the statement, not the attribution verb. If an utterance consists of an attribution verb only, without including the reported statement, the main predicate is the attribution verb.

Note: We rely on an existing pre-annotation for sentence (utterances) here. If utterances are to be manually segmented, then attribution and statement should be put in distinct utterances if and only if the statement is a complete sentence. Normally, this occurs with direct speech only. Also, reported statements interrupted by an attribution verb should not be segmented, then.

In the following example, the main predicate is “Judge O’Kicki unexpectedly awarded him an additional $100,000”, although the syntactic head is “says” (in the attribution clause “he says”). Note that this is a relative clause. The attribution verb is likewise modified by a temporal relative clause (“When … in June 1983”), but only amodifying adverbial clause, not part of the attribution.

Note: If an utterance with attribution carries multiple relative clauses, the comment should clarify which is considered the main predicate.

In the following example, the main predicate is the reported statement in the first relative clause (“the 90-cent-an-hour rise … is too small for the working poor”). In line with UD conventions, we consider the coordinated main clause (“opponents argued …”) to be subordinate to the first main clause.

The following table provides a mapping between AURIS relations and other schemas, based on Bunt and Prasad (2016). AURIS definitions are primarily based on (descriptions and applications of) ISO 24617-8 and guidelines for PDTB1, PDTB2 and PDTB3.

| AURIS | ISO 24617-8 | PDTB2 (PDTB3) | SDRT | RST (RSTDTB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ADVERSATIVITY |

COMPARISON | |||

- Concession |

Concession | Concession | (Contrast) | Concession (Antithesis, Preference) |

- expectation-raiser |

Concession/Expectation-raiser | Expectation (Concession.arg1-as-denier) | ||

- contra-expectation |

Concession/Expectation-denier | Contra-Expectation (Concession.arg2-as-denier) | ||

- concession |

Concession | Concession | ||

- Contrast |

Contrast | Contrast, juxtaposition, opposition | Contrast | Contrast (Comparison) |

CONTINGENCY |

CONTINGENCY | |||

- Causal |

Cause | Cause | ||

- reason |

Cause/Reason | Cause.reason, justification, explanation | Explanation | Vol./Non-vol. Cause, Evidence, Justify (Explanation-argumentation, Reason) |

- result |

Cause/Result | Cause.result | Result | Vol./Non-vol. Result |

- cause |

Cause | Cause | ||

- Conditional |

Condition | |||

- condition |

Condition/Antecedent | Condition | (Conditional) | Condition (Hypothetical) |

- consequence |

Condition/Consequent | (inverse of Condition) | Consequence | (Contingency) |

- Negative_Condition |

Negative Condition | |||

- neg_condition |

Negative Condition/Negated Antecedent | Condition (Negative Condition) | (Conditional) | |

- neg_consequence |

Negative Condition/Consequent | (inverse of Condition) | Consequence | Otherwise |

- Purpose |

Purpose | (Purpose) | Purpose | |

- goal |

Purpose/Goal | Result (Purpose.Arg2-as-goal) | (Explanation, Goal) | |

- enablement |

Purpose/Enablement | (Purpose.Arg1-as-goal) | ||

TEMPORAL |

TEMPORAL | |||

- Synchrony |

Synchrony | Synchronuous | (Temporal-same-time) | |

- Asynchrony |

Asynchrony | Sequence | ||

- before |

Asynchrony/Before | precedence | (Precondition, Flashback) | (Temporal-before, Inverted-sequence) |

- after |

Asynchrony/After | succession | Narration | (Temporal-after, Sequence) |

EXPANSION |

EXPANSION | |||

- Exception |

Exception | Exception | ||

- regular |

Exception/Regular | (Exception.Arg1-as-excpt) | ||

- exception |

Exception/Exception | Exception (Arg2-as-excpt) | ||

- Substitution |

Substitution | Antithesis | ||

- disfavoured |

Substitution/Disfavoured-alternative | (Substitution.Arg1-as-Subst) | ||

- favoured |

Substitution/Favoured-alternative | Chosen-alternative (Substitution.Arg2-as-Subst) | ||

- Exemplification |

Exemplification | |||

- set |

Exemplification/Set | (Instantiation.Arg1-as-instance) | ||

- instance |

Exemplification/Instance | Instantiation (Arg2-as-instance) | Elaboration | Elaboration (set-member, Example) |

- Elaboration |

Elaboration | (Level-of-detail) | ||

- broad |

Elaboration/Broad | Generalization (Level-of-detail.Arg1-as-detail) | ||

- specific |

Elaboration/Specific | Restatement.specification (Level-of-detail.Arg2-as-detail) | Elaboration | Elaboration (general-specific, whole-part, process-step; Conclusion) |

- Manner |

Manner | (Manner) | Elaboration | |

- means |

Manner/Means | (Manner.Arg2-as-manner) | (Means, Manner) | |

- achievement |

Manner/Achievement | (Manner.Arg1-as-manner) | ||

- Restatement |

Restatement | Restatement.equivalence (Equivalence) | Elaboration | Restatement (Summary) |

- Disjunction |

Disjunction | conjunctive, disjunctive | Alternation | Joint (Disjunction) |

- Conjunction |

Conjunction | Conjunction, List | Continuation | Joint (List) |

- Similarity |

Conjunction (Similarity) | Parallel | (Analogy, Proportion) | |

- Hypophora |

n/a | n/a (Hypophora) | ||

- Attribution |

n/a | (Attribution) | ||

DIALOG |

ISO 24617-2, communicative functions | |||

- Functional-Dependence |

Functional-dependence/dependent-act | |||

- answer |

ISO 24617-2: Answer |

|||

- offer |

ISO 24617-2: Offer |

|||

- address suggest |

ISO 24617-2: Address Suggest |

|||

- agreement |

ISO 24617-2: Agreement |

|||

- disagreement |

ISO 24617-2: Disagreement |

|||

- dependent-act |

other dialog act) | |||

- Feedback |

Feedback-dependence/feedback-act | |||

| EntRel | Expansion/Entity description | EntRel | Background, Elaboration | Elaboration (object-attribute, additional) |

Harry Bunt, Jan Alexandersson, Jae-Woong Choe, Alex Chengyu Fang, Koiti Hasida, Volha Petukhova, Andrei Popescu-Belis and David Traum (2017), ISO 24617-2: A semantically-based standard for dialogue annotation. LREC 2012.

Harry Bunt and Prasad, Rashmi (2016), ISO DR-Core (ISO 24617-8), Core concepts for the annotation of discourse relations, In: Proceedings 12th Joint ACL-ISO Workshop on Interoperable Semantic Annotation (ISA-12), p. 45-54

Harry Bunt, Emer Gilmartin, Simon Keizer, Catherine Pelachaud, Volha Petukhova, Laurent Prévot, and Mariët Theune (2018), Downward compatible revision of dialogue annotation. In Proceedings 14th Joint ACL-ISO Workshop on Interoperable Semantic Annotation, pp. 21-34. 2018.

Harry Bunt, Volha Petukhova, Andrei Malchanau, Alex Fang, and Kars Wijnhoven (2019), The DialogBank: dialogues with interoperable annotations. Language Resources and Evaluation 53 (2019): 213-249.

Harry Bunt, Volha Petukhova, Emer Gilmartin, Catherine Pelachaud, Alex Fang, et al. (2020), The ISO Standard for Dialogue Act Annotation, Second Edition. Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, May 2020, Marseille, France.

ISO (2010), Language resource management — Semantic annotation framework — Part 2: Dialogue acts, ISO/TC37/SC4 N723 Date: 2010-07-14, ISO/DIS 24617-2, ISO/TC 37/SC 4/WG 2, pre-publication draft from https://semantic-annotation.uvt.nl/DIS24617-2.pdf, referenced as ISO/DIS 24617-2

Rashmi Prasad, Eleni Miltsakaki, Nikhil Dinesh, Alan Lee, Aravind Joshi, Livio Robaldo (2007), The Penn Discourse Treebank 2.0 Annotation Manual, December 17, 2007, https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~elenimi/pdtb-manual.pdf, accessed 2023-11-09

Rashmi Prasad and Harry Bunt (2015), Semantic Relations in Discourse: The Current State of ISO 24617-8, Proceedings of the 11th Joint ACL-ISO Workshop on Interoperable Semantic Annotation (ISA-11), https://aclanthology.org/W15-0210

Rashmi Prasad, Katherine Forbey-Riley and Alan Lee (2017), Towards Full Text Shallow Discourse Relation Annotation: Experiments with Cross-Paragraph Implicit Relations in the PDTB, Proceedings of the SIGDIAL 2017 Conference, pages 7–16, Saarbrücken, Germany, 15-17 August 2017.

Bonnie Webber, Rashmi Prasad, Alan Lee, Aravind Joshi (2019a), The Penn Discourse Treebank 3.0 Annotation Manual, Language Data Consortium, https://catalog.ldc.upenn.edu/docs/LDC2019T05/PDTB3-Annotation-Manual.pdf, accessed 2023-11-13

Bonnie Webber, Rashmi Prasad and Alan Lee (2019b), Ambiguity in Explicit Discourse Connectives, COLING-2019, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Sebastian Żurowski, Daniel Ziembicki, Aleksandra Tomaszewska, Maciej Ogrodniczuk and Agata Drozd (2023), Adopting ISO 24617-8 for Discourse Relations Annotation in Polish: Challenges and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Language, Data and Knowledge (pp. 482-492).